These excerpts have been taken from Satswarup dasa

Goswami’s Prabhupada-lilamrita ch 11-12.

With the manuscript for Volume Three complete

and with the money to print it, Bhaktivedanta Swami once again entered the

printing world, purchasing paper, correcting proofs, and keeping the printer on

schedule so that the book would be finished by January 1965. Thus, by his

persistence, he who had almost no money of his own managed to publish his third

large hardbound volume within a little more than two years. At this rate, with

his respect in the scholarly world increasing, he might soon become a

recognized figure amongst his countrymen. But he had his vision set on the

West. And with the third volume now printed, he felt he was at last prepared.

He was sixty-nine and would have to go soon. It had been more than forty years

since Shrila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati had first asked a young householder in

Calcutta to preach Krishna consciousness in the West. At first it had seemed

impossible to Abhay Charan, who had so recently entered family

responsibilities. That obstacle, however, had long ago been removed, and for

more than ten years he had been free to travel. But he had been penniless (and

still was). And he had wanted first to publish some volumes of

Shrimad-Bhagavatam to take with him; it had seemed necessary if he were to do

something solid. Now, by Krishna’s grace, three volumes were on hand.

Shrila Prabhupada: I planned that I must go to America.

Generally they go to London, but I did not want to go to London. I was simply

thinking how to go to New York. I was scheming, “Whether I shall go this way,

through Tokyo, Japan, or that way? Which way is cheaper?” That was my proposal.

And I was targeting to New York always. Sometimes I was dreaming that I have

come to New York.

Then Bhaktivedanta Swami met Mr. Agarwal, a Mathura

businessman, and mentioned to him in passing, as he did to almost everyone he

met, that he wanted to go to the West. Although Mr. Agarwal had known

Bhaktivedanta Swami for only a few minutes, he volunteered to try to get him a

sponsor in America. It was something Mr. Agarwal had done a number of times;

when he met a sadhu who mentioned something about going abroad to teach Hindu

culture, he would ask his son Gopal, an engineer in Pennsylvania, to send back

a sponsorship form. When Mr. Agarwal volunteered to help in this way,

Bhaktivedanta Swami urged him please to do so.

Shrila Prabhupada: I did not say anything

seriously to Mr. Agarwal, but perhaps he took it very seriously. I asked him,

“Well, why don’t you ask your son Gopal to sponsor so that I can go there? I

want to preach there.” But Bhaktivedanta Swami knew he could not simply dream

of going to the West; he needed money. In March 1965 he made another visit to

Bombay, attempting to sell his books. Again he stayed at the free dharmasala,

Premkutir. But finding customers was difficult. He met Paramananda Bhagwani, a

librarian at Jai Hind College, who purchased books for the college library and

then escorted Bhaktivedanta Swami to a few likely outlets.

Mr. Bhagwani: I took him to the Popular Book Depot at Grant

Road to help him in selling books, but they told us they couldn’t stock the

books because they don’t have much sales on religion. Then we went to another

shop nearby, and the owner also regretted his inability to sell the books. Then

he went to Sadhuvela, near Mahalakshmi temple, and we met the head of the

temple there. He, of course, welcomed us. They have a library of their own, and

they stock religious books, so we approached them to please keep a set there in

their library. They are a wealthy asrama, and yet he also expressed his

inability.

Bhaktivedanta Swami returned to Delhi, pursuing

the usual avenues of bookselling and looking for whatever opportunity might

arise. And to his surprise, he was contacted by the Ministry of External

Affairs and informed that his No Objection certificate for going to the U.S.

was ready. Since he had not instigated any proceedings for leaving the country,

Bhaktivedanta Swami had to inquire from the ministry about what had happened.

They showed him the Statutory Declaration Form signed by Mr. Gopal Agarwal of

Butler, Pennsylvania; Mr. Agarwal solemnly declared that he would bear the

expenses of Bhaktivedanta Swami during his stay in the U.S.

Shrila Prabhupada: Whatever the correspondence

was there between the father and son, I did not know. I simply asked him, “Why

don’t you ask your son Gopal to sponsor?” And now, after three or four months,

the No Objection certificate was sent from the Indian Consulate in New York to

me. He had already sponsored my arrival there for one month, and all of a

sudden I got the paper.

At his father’s request, Gopal Agarwal had done as he had

done for several other sadhus, none of whom had ever gone to America. It was

just a formality, something to satisfy his father. Gopal had requested a form

from the Indian Consulate in New York, obtained a statement from his employer

certifying his monthly salary, gotten a letter from his bank showing his

balance as of April 1965, and had the form notarized. It had been stamped and

approved in New York and sent to Delhi. Now Bhaktivedanta Swami had a sponsor.

But he still needed a passport, visa, P-form, and travel fare.

The passport was not very difficult to obtain. Krishna

Pandit helped, and by June 10 he had his passport. Carefully, he penned in his

address at the Radha-Krishna temple in Chippiwada and wrote his father’s name,

Gour Mohan De. He asked Krishna Pandit also to pay for his going abroad, but

Krishna Pandit refused, thinking it against Hindu principles for a sadhu to go

abroad—and also very expensive.

With his passport and sponsorship papers,

Bhaktivedanta Swami went to Bombay, not to sell books or raise funds for

printing; he wanted a ticket for America. Again he tried approaching Sumati

Morarji. He showed his sponsorship papers to her secretary, Mr. Choksi, who was

impressed and who went to Mrs. Morarji on his behalf. “The Swami from

Vrindavana is back,” he told her. “He has published his book on your donation.

He has a sponsor, and he wants to go to America. He wants you to send him on a

Scindia ship.” Mrs. Morarji said no, the Swamiji was too old to go to the

United States and expect to accomplish anything. As Mr. Choksi conveyed to him

Mrs. Morarji’s words, Bhaktivedanta Swami listened disapprovingly. She wanted

him to stay in India and complete the Shrimad-Bhagavatam. Why go to the States?

Finish the job here.

But Bhaktivedanta Swami was fixed on going. He told Mr.

Choksi that he should convince Mrs. Morarji. He coached Mr. Choksi on what he

should say: “I find this gentleman very inspired to go to the States and preach

something to the people there…” But when he told Mrs. Morarji, she again said

no. The Swami was not healthy. It would be too cold there. He might not be able

to come back, and she doubted whether he would be able to accomplish much

there. People in America were not so cooperative, and they would probably not

listen to him. Exasperated with Mr. Choksi’s ineffectiveness, Bhaktivedanta

Swami demanded a personal interview. It was granted, and a gray-haired,

determined Bhaktivedanta Swami presented his emphatic request: “Please give me

one ticket.”

Sumati Morarji was concerned. “Swamiji, you are so old—you

are taking this responsibility. Do you think it is all right?”

“No,” he reassured her, lifting his hand as if

to reassure a doubting daughter, “it is all right.” “But do you know what my

secretaries think? They say, “Swamiji is going to die there.’”

Bhaktivedanta made a face as if to dismiss a foolish rumor.

Again he insisted that she give him a ticket. “All right,” she said. “Get your

P-form, and I will make an arrangement to send you by our ship.” Bhaktivedanta

Swami smiled brilliantly and happily left her offices, past her amazed and

skeptical clerks. A “P-form”—another necessity for an Indian national who wants

to leave the country—is a certificate given by the State Bank of India,

certifying that the person has no excessive debts in India and is cleared by

the banks. That would take a while to obtain. And he also did not yet have a

U.S. visa. He needed to pursue these government permissions in Bombay, but he

had no place to stay. So Mrs. Morarji agreed to let him reside at the Scindia

Colony, a compound of apartments for employees of the Scindia Company.

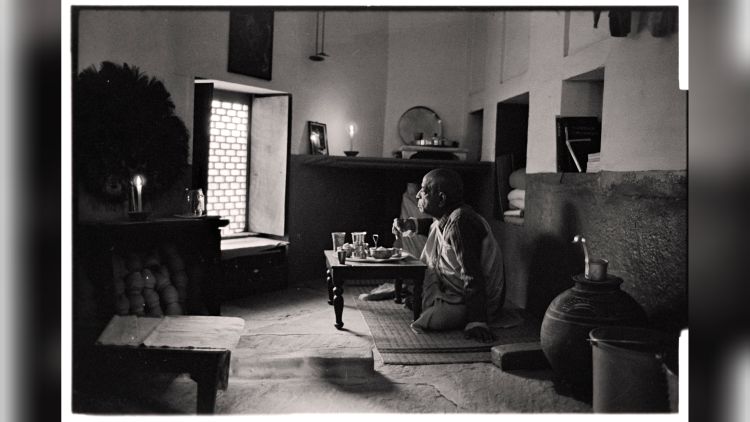

He stayed in a small, unfurnished apartment

with only his trunk and typewriter. The resident Scindia employees all knew

that Mrs. Morarji was sending him to the West, and some of them became

interested in his cause. They were impressed, for although he was so old, he

was going abroad to preach. He was a special sadhu, a scholar. They heard from

him how he was taking hundreds of copies of his books with him, but no money.

He became a celebrity at the Scindia Colony. Various families brought him rice,

sabji, and fruit. They brought so much that he could not eat it all, and he

mentioned this to Mr. Choksi. Just accept it and distribute it, Mr. Choksi

advised. Bhaktivedanta Swami then began giving remnants of his food to the

children. Some of the older residents gathered to hear him as he read and spoke

from Shrimad-Bhagavatam. Mr. Vasavada, the chief cashier of Scindia, was

particularly impressed and came regularly to learn from the sadhu. Mr. Vasavada

obtained copies of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s books and read them in his home.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s apartment shared a roofed-in veranda

with Mr. Nagarajan, a Scindia office worker, and his wife.

Mrs. Nagarajan: Every time when I passed that

way, he used to be writing or chanting. I would ask him, “Swamiji, what are you

writing?” He used to sit near the window and one after another was translating

the Sanskrit. He gave me two books and said, “Child, if you read this book, you

will understand.” We would have discourses in the house, and four or five

Gujarati ladies used to come. At one of these discourses he told one lady that

those who wear their hair parted on the side—that is not a good idea. Every

Indian lady should have her hair parted in the center. They were very fond of

listening and very keen to hear his discourse.

Every day he would go out trying to get his visa and P-form

as quickly as possible, selling his books, and seeking contacts and supporters

for his future Shrimad-Bhagavatam publishing. Mr. Nagarajan tried to help.

Using the telephone directory, he made a list of wealthy business and

professional men who were Vaishnavas and might be inclined to assist.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s neighbors at Scindia Colony observed him coming home dead

tired in the evening. He would sit quietly, perhaps feeling morose, some

neighbors thought, but after a while he would sit up, rejuvenated, and start

writing.

Mrs. Nagarajan: When he came home we used to

give him courage, and we used to tell him, “Swamiji, one day you will achieve

your target.” He would say, “Time is still not right. Time is still not right.

They are all ajnanis. They don’t understand. But still I must carry on.”

Sometimes I would go by, and his cadar would be on the

chair, but he would be sitting on the windowsill. I would ask him, “Swamiji,

did you have any good contacts?” He would say, “Not much today. I didn’t get

much, and it is depressing. Tomorrow Krishna will give me more details.” And he

would sit there quietly.

After ten minutes, he would sit in his chair

and start writing. I would wonder how Swamiji was so tired in one minute and in

another minuten Even if he was tired, he was not defeated. He would never speak

discouragement. And we would always encourage him and say, “If today you don’t

get it, tomorrow you will definitely meet some people, and they will encourage

you.” And my friends used to come in the morning and in the evening for

discourse, and they would give namaskara and fruits.

Mr. Nagarajan: His temperament was very adjustable and

homely. Our friends would offer a few rupees. He would say, “All right. It will

help.” He used to walk from our colony to Andheri station. It is two

kilometers, and he used to go there without taking a bus, because he had no

money.

Bhaktivedanta Swami had a page printed entitled “My

Mission,” and he would show it to influential men in his attempts to get

further financing for Shrimad-Bhagavatam. The printed statement proposed that

God consciousness was the only remedy for the evils of modern materialistic

society. Despite scientific advancement and material comforts, there was no

peace in the world; therefore, Bhagavad-gita and Shrimad-Bhagavatam, the glory

of India, must be spread all over the world.

Mrs. Morarji asked Bhaktivedanta Swami if he would read

Shrimad-Bhagavatam to her in the evening. He agreed. She began sending her car

for him at six o’clock each evening, and they would sit in her garden, where he

would recite and comment on the Bhagavatam.

Mrs. Morarji: He used to come in the evening

and sing the verses in rhythmic tunes, as is usually done with the Bhagavatam.

And certain points—when you sit and discuss, you raise so many points—he was

commenting on certain points, but it was all from the Bhagavatam. So he used to

sit and explain to me and then go. He could give time, and I could hear him.

That was for about ten or fifteen days.

His backing by Scindia and his sponsorship in the U.S. were

a strong presentation, and with the help of the people at Scindia he obtained

his visa on July 28, 1965. But the P-form proceedings went slowly and even

threatened to be a last, insurmountable obstacle.

Shrila Prabhupada: Formerly there was no

restriction for going outside. But for a sannyasi like me, I had so much

difficulty obtaining the government permission to go out. I had applied for the

P-form sanction, but no sanction was coming. Then I went to the State Bank of

India. The officer was Mr. Martarchari. He told me, “Swamiji, you are sponsored

by a private man. So we cannot accept. If you were invited by some institution,

then we could consider. But you are invited by a private man for one month. And

after one month, if you are in difficulty, there will be so many obstacles.”

But I had already prepared everything to go. So I said, “What have you done?”

He said, “I have decided not to sanction your P-form.” I said, “No, no, don’t

do this. You better send me to your superior. It should not be like that.”

So he took my request, and he sent the file to

the chief official of foreign exchange—something like that. So he was the

supreme man in the State Bank of India. I went to see him. I asked his

secretary, “Do you have such-and-such a file. You kindly put it to Mr. Rao. I

want to see him.” So the secretary agreed, and he put the file, and he put my

name down to see him. I was waiting. So Mr. Rao came personally. He said,

“Swamiji, I passed your case. Don’t worry.”

Following Mrs. Morarji’s instruction, her secretary, Mr.

Choksi, made final arrangements for Bhaktivedanta Swami. Since he had no warm

clothes, Mr. Choksi took him to buy a wool jacket and other woolen clothes. Mr.

Choksi spent about 250 rupees on new clothes, including some new dhotis. At

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s request, Mr. Choksi printed five hundred copies of a

small pamphlet containing the eight verses written by Lord Chaitanya and an

advertisement for Shrimad-Bhagavatam, in the context of an advertisement for

the Scindia Steamship Company.

Mr. Choksi: I asked him, “Why couldn’t you go

earlier? Why do you want to go now to the States, at this age?” He replied

that, “I will be able to do something good, I am sure.” His idea was that

someone should be there who would be able to go near people who were lost in

life and teach them and tell them what the correct thing is. I asked him so

many times, “Why do you want to go to the States? Why don’t you start something

in Bombay or Delhi or Vrindavana?” I was teasing him also: “You are interested

in seeing the States. Therefore, you want to go. All Swamijis want to go to the

States, and you want to enjoy there.” He said, “What I have got to see? I have

finished my life.”

But sometimes he was hot-tempered. He used to get angry at

me for the delays. “What is this nonsense?” he would say. Then I would

understand: he is getting angry now. Sometimes he would say, “Oh, Mrs. Morarji

has still not signed this paper? She says come back tomorrow, we will talk

tomorrow! What is this? Why this daily going back?” He would get angry. Then I

would say, “You can sit here.” But he would say, “How long do I have to sit?”

He would become impatient. Finally Mrs. Morarji scheduled a place for him on

one of her ships, the Jaladuta, which was sailing from Calcutta on August 13.

She had made certain that he would travel on a ship whose captain understood the

needs of a vegetarian and a brahmana. Mrs. Morarji told the Jaladuta’s captain,

Arun Pandia, to carry extra vegetables and fruits for the Swami. Mr. Choksi

spent the last two days with Bhaktivedanta Swami in Bombay, picking up the

pamphlets at the press, purchasing clothes, and driving him to the station to

catch the train for Calcutta.

He arrived in Calcutta about two weeks before

the Jaladuta’s departure. Although he had lived much of his life in the city,

he now had nowhere to stay. It was as he had written in his

“Vrindavana-bhajana”: “I have my wife, sons, daughters, grandsons, everything,

/ But I have no money, so they are a fruitless glory.” Although in this city he

had been so carefully nurtured as a child, those early days were also gone

forever: “Where have my loving father and mother gone to now? / And where are

all my elders, who were my own folk? / Who will give me news of them, tell me

who? / All that is left of this family life is a list of names.”

Out of the hundreds of people in Calcutta whom

Bhaktivedanta Swami knew, he chose to call on Mr. Sisir Bhattacharya, the

flamboyant kirtana singer he had met a year before at the governor’s house in

Lucknow. Mr. Bhattacharya was not a relative, not a disciple, nor even a close

friend; but he was willing to help. Bhaktivedanta Swami called at his place and

informed him that he would be leaving on a cargo ship in a few days; he needed

a place to stay, and he would like to give some lectures. Mr. Bhattacharya

immediately began to arrange a few private meetings at friends’ homes, where he

would sing and Bhaktivedanta Swami would then speak.

Mr. Bhattacharya thought the sadhu’s leaving

for America should make an important news story. He accompanied Bhaktivedanta

Swami to all the newspapers in Calcutta—the Hindustan Standard, the Amrita

Bazar Patrika, the Jugantas, the Statesman, and others. Bhaktivedanta Swami had

only one photograph, a passport photo, and they made a few copies for the

newspapers. Mr. Bhattacharya would try to explain what the Swami was going to

do, and the news writers would listen. But none of them wrote anything. Finally

they visited the Dainik Basumati, a local Bengali daily, which agreed to print

a small article with Bhaktivedanta Swami’s picture.

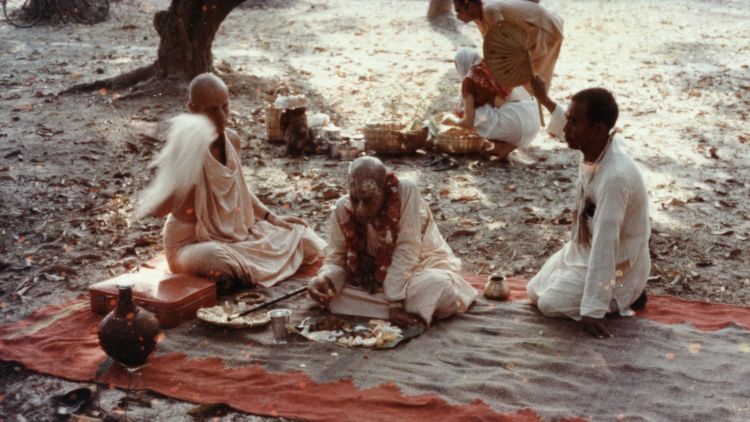

A week before his departure, on August 6,

Bhaktivedanta Swami traveled to nearby Mayapur to visit the samadhi of Shrila

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati. Then he returned to Calcutta, where Mr. Bhattacharya

continued to assist him with his final business and speaking engagements. Mr.

Bhattacharya: We just took a hired taxi to this place and that place. And he

would go for preaching. I never talked to him during the preaching, but once

when I was coming back from the preaching, I said, “You said this thing about

this. But I tell you it is not this. It is this.” I crossed him in something or

argued. And he was furious. Whenever we argued and I said, “No, I think this is

this,” then he was shouting. He was very furious. He said, “You are always

saying, “I think, I think, I think.’ What is the importance of what you think?

Everything is what you think. But it doesn’t matter. It matters what sastra

says. You must follow.” I said, “I must do what I think, what I feel—that is

important.” He said, “No, you should forget this. You should forget your desire.

You should change your habit. Better you depend on sastras. You follow what

sastra wants you to do, and do it. I am not telling you what I think, but I am

repeating what the sastra says.”

As the day of his departure approached,

Bhaktivedanta Swami took stock of his meager possessions. He had only a

suitcase, an umbrella, and a supply of dry cereal. He did not know what he

would find to eat in America; perhaps there would be only meat. If so, he was

prepared to live on boiled potatoes and the cereal. His main baggage, several

trunks of his books, was being handled separately by Scindia Cargo. Two hundred

three-volume sets—the very thought of the books gave him confidence.

When the day came for him to leave, he needed that

confidence. He was making a momentous break with his previous life, and he was

dangerously old and not in strong health. And he was going to an unknown and

probably unwelcoming country. To be poor and unknown in India was one thing.

Even in these Kali-yuga days, when India’s leaders were rejecting Vedic culture

and imitating the West, it was still India; it was still the remains of Vedic

civilization. He had been able to see millionaires, governors, the prime

minister, simply by showing up at their doors and waiting. A sannyasi was respected;

the Shrimad-Bhagavatam was respected. But in America it would be different. He

would be no one, a foreigner. And there was no tradition of sadhus, no temples,

no free asramas. But when he thought of the books he was

bringing—transcendental knowledge in English—he became confident. When he met

someone in America he would give him a flyer: ““Shrimad Bhagwatam,’ India’s

Message of Peace and Goodwill.”

It was August 13, just a few days before

Janmashtami, the appearance day anniversary of Lord Krishna—the next day would

be his own sixty-ninth birthday. During these last years, he had been in

Vrindavana for Janmashtami. Many Vrindavana residents would never leave there;

they were old and at peace in Vrindavana. Bhaktivedanta Swami was also

concerned that he might die away from Vrindavana. That was why all the

Vaishnava sadhus and widows had taken vows not to leave, even for

Mathura—because to die in Vrindavana was the perfection of life. And the Hindu

tradition was that a sannyasi should not cross the ocean and go to the land of

the mlecchas. But beyond all that was the desire of Shrila Bhaktisiddhanta

Sarasvati, and his desire was nondifferent from that of Lord Krishna. And Lord

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu had predicted that the chanting of Hare Krishna would be

known in every town and village of the world.

Bhaktivedanta Swami took a taxi down to the

Calcutta port. A few friends and admirers, along with his son Vrindavan,

accompanied him. He writes in his diary: “Today at 9 a.m. embarked on M.V.

Jaladuta. Came with me Bhagwati, the Dwarwan of Scindia Sansir, Mr. Sen Gupta,

Mr. Ali and Vrindaban.” He was carrying a Bengali copy of

Chaitanya-caritamrita, which he intended to read during the crossing. Somehow

he would be able to cook on board. Or if not, he could starve— whatever Krishna

desired. He checked his essentials: passenger ticket, passport, visa, P-form,

sponsor’s address. Finally it was happening.

Shrila Prabhupada: With what great difficulty I

got out of the country! Some way or other, by Krishna’s grace, I got out so I

could spread the Krishna consciousness movement all over the world. Otherwise,

to remain in India—it was not possible. I wanted to start a movement in India,

but I was not at all encouraged.

The black cargo ship, small and weathered, was

moored at dockside, a gangway leading from the dock to the ship’s deck. Indian

merchant sailors curiously eyed the elderly saffron-dressed sadhu as he spoke

last words to his companions and then left them and walked determinedly toward

the boat.

For thousands of years, krishna-bhakti had been known only

in India, not outside, except in twisted, faithless reports by foreigners. And

the only swamis to have reached America had been nondevotees, Mayavadi impersonalists.

But now Krishna was sending Bhaktivedanta Swami as His emissary.

SPL 12: The Journey to America

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Journey to America

Today the ship is plying very smoothly. I feel

today better. But I am feeling separation from Shri Vrindaban and my Lords Shri

Govinda, Gopinath, Radha Damodar. My only solace is Shri Chaitanya Charitamrita

in which I am tasting the nectarine of Lord Chaitanya’s lila. I have left

Baharatabhumi just to execute the order of Shri Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, in

pursuance of Lord Chaitanya’s order. I have no qualification, but have taken up

the risk just to carry out the order of His Divine Grace. I depend fully on

Their mercy, so far away from Vrindaban.

—Jaladuta diary

September 10, 1965

The Jaladuta is a regular cargo carrier of the

Scindia Steam Navigation Company, but there is a passenger cabin aboard. During

the voyage from Calcutta to New York in August and September of 1965, the cabin

was occupied by “Shri Abhoy Charanaravinda Bhaktivedanta Swami,” whose age was

listed as sixty-nine and who was taken on board bearing “a complimentary ticket

with food.”

The Jaladuta, under the command of Captain Arun Pandia,

whose wife was also aboard, left at 9:00 A.M. on Friday, August 13. In his

diary, Shrila Prabhupada noted: “The cabin is quite comfortable, thanks to Lord

Shri Krishna for enlightening Sumati Morarji for all these arrangements. I am

quite comfortable.” But on the fourteenth he reported: “Seasickness, dizziness,

vomiting—Bay of Bengal. Heavy rains. More sickness.”

On the nineteenth, when the ship arrived at

Colombo, Ceylon (now Shri Lanka), Prabhupada was able to get relief from his

seasickness. The captain took him ashore, and he traveled around Colombo by

car. Then the ship went on toward Cochin, on the west coast of India.

Janmashtami, the appearance day of Lord Krishna, fell on the twentieth of

August that year. Prabhupada took the opportunity to speak to the crew about

the philosophy of Lord Krishna, and he distributed prasadam he had cooked himself.

August 21 was his seventieth birthday, observed (without ceremony) at sea. That

same day the ship arrived at Cochin, and Shrila Prabhupada’s trunks of

Shrimad-Bhagavatam volumes, which had been shipped from Bombay, were loaded on

board.

By the twenty-third the ship had put out to the

Red Sea, where Shrila Prabhupada encountered great difficulty. He noted in his

diary: “Rain, seasickness, dizziness, headache, no appetite, vomiting.” The

symptoms persisted, but it was more than seasickness. The pains in his chest

made him think he would die at any moment. In two days he suffered two heart

attacks. He tolerated the difficulty, meditating on the purpose of his mission,

but after two days of such violent attacks he thought that if another were to

come he would certainly not survive.

On the night of the second day, Prabhupada had a dream. Lord

Krishna, in His many forms, was rowing a boat, and He told Prabhupada that he

should not fear, but should come along. Prabhupada felt assured of Lord

Krishna’s protection, and the violent attacks did not recur.

The Jaladuta entered the Suez Canal on September 1 and

stopped in Port Sa’id on the second. Shrila Prabhupada visited the city with

the captain and said that he liked it. By the sixth he had recovered a little

from his illness and was eating regularly again for the first time in two

weeks, having cooked his own kichari and puris. He reported in his diary that

his strength renewed little by little.

Thursday, September 9

To 4:00 this afternoon, we have crossed over the Atlantic

Ocean for twenty-four hours. The whole day was clear and almost smooth. I am

taking my food regularly and have got some strength to struggle. There is also

a slight tacking of the ship and I am feeling a slight headache also. But I am

struggling and the nectarine of life is Shri Chaitanya Charitamrita, the source

of all my vitality.

Friday, September 10

Today the ship is plying very smoothly. I feel today better.

But I am feeling separation from Shri Vrindaban and my Lords Shri Govinda, Gopinath,

Radha Damodar. The only solace is Shri Chaitanya Charitamrita in which I am

tasting the nectarine of Lord Chaitanya’s lila [pastimes]. I have left

Bharatabhumi just to execute the order of Shri Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati in

pursuance of Lord Chaitanya’s order. I have no qualification, but have taken up

the risk just to carry out the order of His Divine Grace. I depend fully on

Their mercy, so far away from Vrindaban.

During the voyage, Shrila Prabhupada sometimes

stood on deck at the ship’s rail, watching the ocean and the sky and thinking

of Chaitanya-caritamrita, Vrindavana-dhama, and the order of his spiritual

master to go preach in the West. Mrs. Pandia, the captain’s wife, whom Shrila

Prabhupada considered to be “an intelligent and learned lady,” foretold Shrila

Prabhupada’s future. If he were to pass beyond this crisis in his health, she

said, it would indicate the good will of Lord Krishna.

The ocean voyage of 1965 was a calm one for the Jaladuta.

The captain said that never in his entire career had he seen such a calm

Atlantic crossing. Prabhupada replied that the calmness was Lord Krishna’s

mercy, and Mrs. Pandia asked Prabhupada to come back with them so that they

might have another such crossing. Shrila Prabhupada wrote in his diary, “If the

Atlantic would have shown its usual face, perhaps I would have died. But Lord

Krishna has taken charge of the ship.”

On September 13, Prabhupada noted in his diary:

“Thirty-second day of journey. Cooked bati kichari. It appeared to be

delicious, so I was able to take some food. Today I have disclosed my mind to

my companion, Lord Shri Krishna. There is a Bengali poem made by me in this

connection.”

This poem was a prayer to Lord Krishna, and it is filled

with Prabhupada’s devotional confidence in the mission that he had undertaken

on behalf of his spiritual master. An English translation of the opening

stanzas follows:*

I emphatically say to you, O brothers, you will

obtain your good fortune from the Supreme Lord Krishna only when Shrimati

Radharani becomes pleased with you.

Shri Shrimad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, who is very

dear to Lord Gauranga [Lord Chaitanya], the son of mother Saci, is unparalleled

in his service to the Supreme Lord Shri Krishna. He is that great, saintly

spiritual master who bestows intense devotion to Krishna at different places

throughout the world.

By his strong desire, the holy name of Lord

Gauranga will spread throughout all the countries of the Western world. In all

the cities, towns, and villages on the earth, from all the oceans, seas,

rivers, and streams, everyone will chant the holy name of Krishna.

As the vast mercy of Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu conquers all

directions, a flood of transcendental ecstasy will certainly cover the land.

When all the sinful, miserable living entities become happy, the Vaishnavas’

desire is then fulfilled.

Although my Guru Maharaja ordered me to

accomplish this mission, I am not worthy or fit to do it. I am very fallen and

insignificant. Therefore, O Lord, now I am begging for Your mercy so that I may

become worthy, for You are the wisest and most experienced of all…

The poem ends:

Today that remembrance of You came to me in a very nice way.

Because I have a great longing I called to You. I am Your eternal servant, and

therefore I desire Your association so much. O Lord Krishna, except for You

there is no means of success.

In the same straightforward, factual manner in

which he had noted the date, the weather, and his state of health, he now

described his helpless dependence on his “companion, Lord Krishna,” and his

absorption in the ecstasy of separation from Krishna. He described the

relationship between the spiritual master and the disciple, and he praised his

own spiritual master, Shri Shrimad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, “by whose strong

desire the holy name of Lord Gauranga will spread throughout all the countries

of the Western world.” He plainly stated that his spiritual master had ordered

him to accomplish this mission of worldwide Krishna consciousness, and feeling

unworthy he prayed to Lord Krishna for strength. The last verses give an

unexpected, confidential glimpse into Shrila Prabhupada’s direct relationship

with Lord Krishna. Prabhupada called on Krishna as his “dear friend” and longed

for the joy of again wandering the fields of Vraja. This memory of Krishna, he

wrote, came because of a great desire to serve the Lord. Externally, Shrila

Prabhupada was experiencing great inconvenience; he had been aboard ship for a

month and had suffered heart attacks and repeated seasickness. Moreover, even

if he were to recover from these difficulties, his arrival in America would

undoubtedly bring many more difficulties. But remembering the desire of his

spiritual master, taking strength from his reading of Chaitanya-caritamrita,

and revealing his mind in his prayer to Lord Krishna, Prabhupada remained

confident.

After a thirty-five-day journey from Calcutta,

the Jaladuta reached Boston’s Commonwealth Pier at 5:30 A.M. on September 17,

1965. The ship was to stop briefly in Boston before proceeding to New York

City. Among the first things Shrila Prabhupada saw in America were the letters

“A & P” painted on a pierfront warehouse. The gray waterfront dawn revealed

the ships in the harbor, a conglomeration of lobster stands and drab buildings,

and, rising in the distance, the Boston skyline.

Prabhupada had to pass through U.S. Immigration

and Customs in Boston. His visa allowed him a three-month stay, and an official

stamped it to indicate his expected date of departure. Captain Pandia invited

Prabhupada to take a walk into Boston, where the captain intended to do some

shopping. They walked across a footbridge into a busy commercial area with old

churches, warehouses, office buildings, bars, tawdry bookshops, nightclubs, and

restaurants. Prabhupada briefly observed the city, but the most significant

thing about his short stay in Boston, aside from the fact that he had now set

foot in America, was that at Commonwealth Pier he wrote another Bengali poem,

entitled “Markine Bhagavata-dharma” (“Teaching Krishna Consciousness in

America”). Some of the verses he wrote on board the ship that day are as

follows:*

My dear Lord Krishna, You are so kind upon this

useless soul, but I do not know why You have brought me here. Now You can do

whatever You like with me.

But I guess You have some business here, otherwise why would

You bring me to this terrible place?

Most of the population here is covered by the material modes

of ignorance and passion. Absorbed in material life they think themselves very

happy and satisfied, and therefore they have no taste for the transcendental

message of Vasudeva [Krishna]. I do not know how they will be able to

understand it.

But I know that Your causeless mercy can make

everything possible, because You are the most expert mystic. How will they

understand the mellows of devotional service? O Lord, I am simply praying for

Your mercy so that I will be able to convince them about Your message. All

living entities have come under the control of the illusory energy by Your

will, and therefore, if You like, by Your will they can also be released from

the clutches of illusion. I wish that You may deliver them. Therefore if You so

desire their deliverance, then only will they be able to understand Your

message…

How will I make them understand this message of

Krishna consciousness? I am very unfortunate, unqualified, and the most fallen.

Therefore I am seeking Your benediction so that I can convince them, for I am

powerless to do so on my own.

Somehow or other, O Lord, You have brought me

here to speak about You. Now, my Lord, it is up to You to make me a success or

failure, as You like. O spiritual master of all the worlds! I can simply repeat

Your message. So if You like You can make my power of speaking suitable for

their understanding.

Only by Your causeless mercy will my words

become pure. I am sure that when this transcendental message penetrates their

hearts, they will certainly feel gladdened and thus become liberated from all

unhappy conditions of life.

O Lord, I am just like a puppet in Your hands.

So if You have brought me here to dance, then make me dance, make me dance, O

Lord, make me dance as You like. I have no devotion, nor do I have any

knowledge, but I have strong faith in the holy name of Krishna. I have been

designated as Bhaktivedanta, and now, if You like, You can fulfill the real

purport of Bhaktivedanta.

Signed—the most unfortunate, insignificant beggar,

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami,

On board the ship Jaladuta, Commonwealth Pier,

Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A.

Dated 18th September 1965.

He was now in America. He was in a major

American city, rich with billions, populated with millions, and determined to

stay the way it was. Prabhupada saw Boston from the viewpoint of a pure devotee

of Krishna. He saw the hellish city life, people dedicated to the illusion of

material happiness. All his dedication and training moved him to give these

people the transcendental knowledge and saving grace of Krishna consciousness,

yet he was feeling weak, lowly, and unable to help them on his own. He was but

“an insignificant beggar” with no money. He had barely survived the two heart

attacks at sea, he spoke a different language, he dressed strangely—yet he had

come to tell people to give up meat-eating, illicit sex, intoxication, and

gambling, and to teach them to worship Lord Krishna, who to them was a mythical

Hindu god. What would he be able to accomplish?

Helplessly he spoke his heart directly to God: “I wish that

You may deliver them. I am seeking Your benediction so that I can convince

them.” And for convincing them he would trust in the power of God’s holy name

and in the Shrimad-Bhagavatam. This transcendental sound would clean away

desire for material enjoyment from their hearts and awaken loving service to

Krishna. On the streets of Boston, Prabhupada was aware of the power of

ignorance and passion that dominated the city; but he had faith in the

transcendental process. He was tiny, but God was infinite, and God was Krishna,

his dear friend.

On the nineteenth of September the Jaladuta

sailed into New York Harbor and docked at a Brooklyn pier, at Seventeenth

Street. Shrila Prabhupada saw the awesome Manhattan skyline, the Empire State

Building, and, like millions of visitors and immigrants in the past, the Statue

of Liberty.

Shrila Prabhupada was dressed appropriately for a resident

of Vrindavana. He wore kanthi-mala (neck beads) and a simple cotton dhoti, and

he carried japa-mala (chanting beads) and an old chadar, or shawl. His

complexion was golden, his head shaven, sikha in the back, his forehead

decorated with the whitish Vaishnava tilaka. He wore pointed white rubber

slippers, not uncommon for sadhus in India. But who in New York had ever seen

or dreamed of anyone appearing like this Vaishnava? He was possibly the first

Vaishnava sannyasi to arrive in New York with uncompromised appearance. Of

course, New Yorkers have an expertise in not giving much attention to any kind

of strange new arrival.

Shrila Prabhupada was on his own. He had a

sponsor, Mr. Agarwal, somewhere in Pennsylvania. Surely someone would be here

to greet him. Although he had little idea of what to do as he walked off the

ship onto the pier—“I did not know whether to turn left or right”—he passed

through the dockside formalities and was met by a representative from

Traveler’s Aid, sent by the Agarwals in Pennsylvania, who offered to take him

to the Scindia ticket office in Manhattan to book his return passage to India.

At the Scindia office, Prabhupada spoke with

the ticket agent, Joseph Foerster, who was impressed by this unusual

passenger’s Vaishnava appearance, his light luggage, and his apparent poverty.

He regarded Prabhupada as a priest. Most of Scindia’s passengers were

businessmen or families, so Mr. Foerster had never seen a passenger wearing the

traditional Vaishnava dress of India. He found Shrila Prabhupada to be “a

pleasant gentleman” who spoke of “the nice accommodations and treatment he had

received aboard the Jaladuta.” Prabhupada asked Mr. Foerster to hold space for

him on a return ship to India. His plans were to leave in about two months, and

he told Mr. Foerster that he would keep in touch. Carrying only forty rupees

cash, which he himself called “a few hours’ spending in New York,” and an

additional twenty dollars he had collected from selling three volumes of the

Bhagavatam to Captain Pandia, Shrila Prabhupada, with umbrella and suitcase in

hand, and still escorted by the Traveler’s Aid representative, set out for the

Port Authority Bus Terminal to arrange for his trip to Butler.

(These excerpts have been taken from Satswarup dasa

Goswami’s Prabhupada-lilamrita ch 11-12.)